Traffic engineering exists because networks are finite. Links have limits, traffic competes, and assumptions eventually collide with physics. Over decades of network evolution, architectures and control systems have come and gone, but the fundamental challenge has not changed:

How to move traffic through a shared infrastructure without exceeding what the network can safely deliver?

In recent years, many networks have drifted away from strategic bandwidth management in favor of looser, tactical approaches. Capacity awareness is too often treated as an implementation detail rather than a design principle. As a result, congestion management shifted from intentional admission to reactive mitigation.

Predictably, the industry has began introducing incremental, tactical mechanisms—better telemetry, faster reroute triggers, smarter queue management—to compensate for that loss. While these tools are useful, they largely operate after contention has already occurred. They address symptoms rather than the underlying question of whether the traffic should have been admitted in the first place.

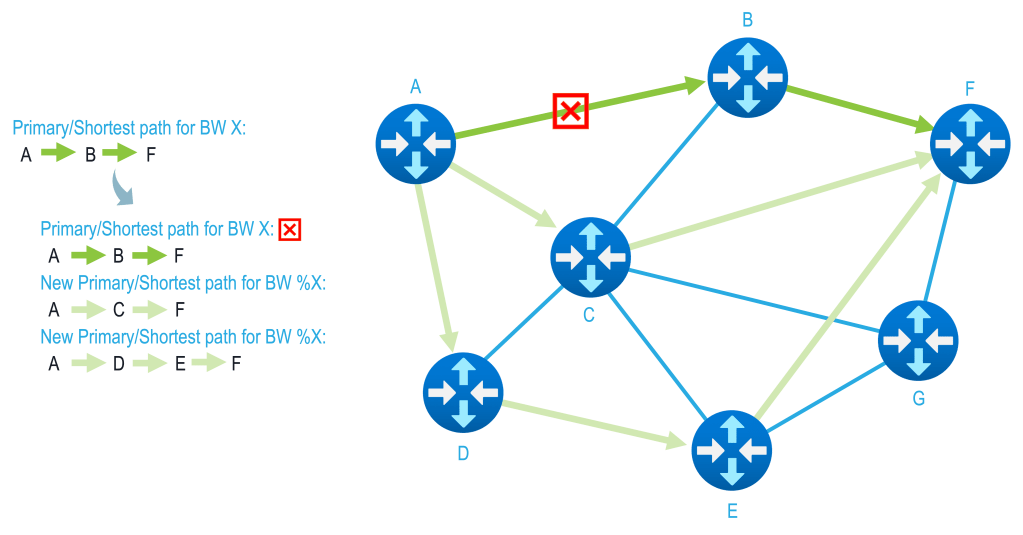

Bandwidth-aware traffic engineering revisits that question directly. Rather than layering corrective behaviors on top of oversubscription, it treats capacity as a first-class constraint and aligns traffic placement with what the network can actually carry.

Traffic is not merely forwarded along a shortest path; it is evaluated against the ability of the network to carry it. This shift defines the difference between reactive congestion management and intentional bandwidth engineering.

Bandwidth as a First-Class Constraint

At its core, bandwidth-aware traffic engineering recognizes that congestion is not a global phenomenon. It occurs at specific links, at specific moments, under specific conditions. Effective systems therefore avoid making broad assumptions based on aggregate models or centralized predictions alone.

Instead, they[nodes] rely on local capacity awareness. Each node(link) within the network evaluates whether it can safely carry additional traffic before accepting it. This creates a chain of independent, deterministic decisions that reflect real conditions rather than theoretical availability. When bandwidth is treated as a first-class constraint, overcommitment becomes an explicit choice rather than an accidental outcome.

Feedback, Not Guesswork

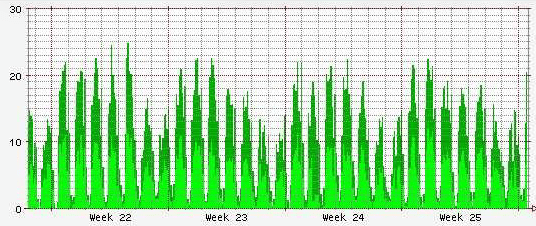

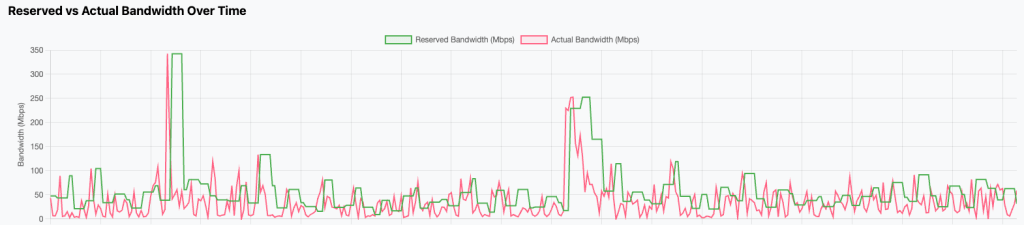

Traffic demand is not static. Applications change behavior, user patterns shift, and growth rarely arrives evenly. Bandwidth-aware systems embrace this dynamism by incorporating feedback loops rather than relying on static provisioning.

Measurement informs adjustment. Adjustment is bounded by policy and physical limits. And those limits are enforced consistently. By favoring incremental change over wholesale reconfiguration, these systems avoid oscillation while still responding to sustained shifts in demand. The network does not chase short-term spikes, nor does it remain blind to long-term trends.

This is control theory applied pragmatically: dampened, observable, and conservative by design.

Change Without Disruption

Not all change requires rerouting, duplication, or churn. One of the strengths of robust bandwidth-aware approaches is their ability to modify allocations in place when the underlying topology remains stable. Rather than tearing down and rebuilding forwarding behavior, the system adjusts the parameters governing existing traffic flows.

This reduces risk. It minimizes transient congestion, avoids unnecessary state duplication, and preserves continuity for applications already in flight. The network evolves gradually, preserving intent while accommodating reality.

Shared Resources Are the Norm

Networks are not collections of isolated paths. They are shared systems where overlap is inevitable. Bandwidth-aware traffic engineering acknowledges this by accounting for shared links/paths explicitly rather than pretending they are exceptional cases.

When multiple traffic flows converge on common infrastructure, their combined impact is considered holistically. This prevents the same capacity from being counted multiple times and allows transitions to occur safely even when paths are only partially disjoint. The goal is not maximal separation, but honest accounting.

Engineering for Failure

Network failures are exactly when bandwidth-aware traffic engineering becomes most critical. When links, nodes, or entire paths disappear, the remaining infrastructure must absorb displaced traffic without exceeding what it can safely carry. In these moments, the ability to understand and intentionally use all available paths in the network is not an optimization—it is a necessity.

Bandwidth-aware systems respond to failure by making capacity explicit at the point where it matters most. As traffic is redistributed, each remaining path is evaluated against its actual ability to carry additional load. This ensures that recovery does not simply shift congestion elsewhere, but instead spreads traffic according to real, available headroom.

Just as importantly, these systems prevent silent degradation. When capacity is exhausted, the network does not pretend otherwise. Limits are surfaced clearly, and tradeoffs become visible to operators and control systems alike. By exposing constraints instead of masking them, bandwidth-aware traffic engineering avoids cascading assumptions that turn partial failures into systemic instability.

Resilience, in this context, is not about avoiding failure—it is about responding to failure with clarity, intent, and respect for the network’s remaining capacity.

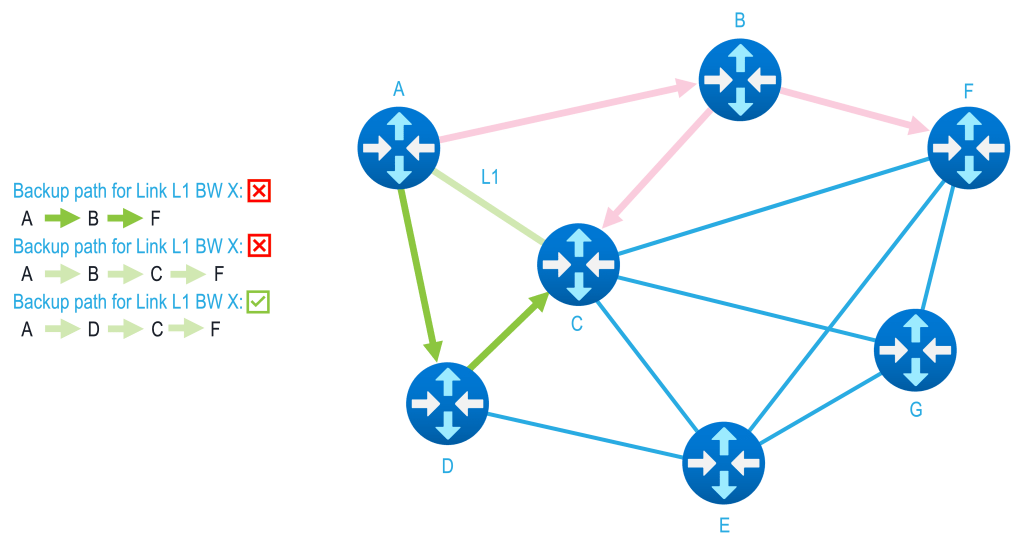

Bandwidth Awareness During Fast Reroute

Fast reroute mechanisms are designed to restore connectivity quickly, in 10’s of milliseconds, by redirecting traffic onto precomputed or locally available alternate paths. Speed is essential—but speed alone is not sufficient. When reroute decisions ignore bandwidth constraints, rapid recovery can simply exchange one failure for another.

During a failure, fast reroute concentrates traffic onto a smaller set of remaining paths. Without explicit accounting, these paths may be oversubscribed immediately, leading to packet loss, queue collapse, and unstable forwarding behavior. From the outside, the network appears “up,” but service quality degrades silently and unevenly. This is not resilience—it is deferred failure.

Bandwidth-aware traffic engineering complements fast reroute by ensuring that recovery paths are evaluated not just for reachability, but for available capacity. Protection is no longer binary; it is conditional. Traffic is steered onto alternate paths that can actually sustain it, and where capacity is limited, that limitation is recognized and exposed.

By protecting and accounting for bandwidth during fast reroute, networks avoid compounding failures under stress. Recovery becomes orderly rather than chaotic, and operators gain confidence that restoration behavior aligns with physical reality. Fast reroute restores connectivity; bandwidth-aware engineering ensures that the restored connectivity is usable.

Human-Scale Visibility

Networks are ultimately operated by people. Tools, automation, and control systems matter, but when something goes wrong, a human still has to understand what the network is doing and why.

Bandwidth-aware traffic engineering helps because it aligns with how engineers already think about networks. Links have finite capacity. Traffic consumes some portion of that capacity. If more traffic is added, something else must give. These relationships are concrete and observable.

When bandwidth is accounted for explicitly, operators can reason about the network in straightforward terms. They can see what is using a link today, how much headroom remains, and what the impact of additional demand would be. Questions like “what is filling this link?” or “can I safely add more traffic here?” have direct answers instead of guesses.

This clarity changes how networks are operated. Decisions become deliberate rather than reactive. Planning replaces firefighting. By removing uncertainty and hidden coupling, bandwidth-aware systems reduce operational stress and lower the risk of mistakes made under pressure.

Predictability Over Perfection

The ultimate objective of bandwidth-aware traffic engineering is not perfect utilization. It is predictable behavior during change. By distributing decision-making, enforcing guardrails, and favoring incremental adjustment, these systems limit blast radius and avoid sudden, destabilizing shifts.

In production environments, predictability is often more valuable than theoretical optimality. Calm networks are easier to operate, easier to scale, and more forgiving of human and systemic imperfections.

Bandwidth-aware traffic engineering is not a single technology or protocol. It is a philosophy grounded in constraint, feedback, and honesty. As networks continue to evolve, these principles remain constant—not because they are fashionable, but because they work.

Disclaimer

The opinions, analyses, and recommendations expressed in any post, comment, or other content on tedigest.com are solely those of the individual authors. They do not represent the official policies, positions, or endorsements of the authors’ current or former employers and affiliated organizations.

Leave a comment