RFC 9522 provides a useful framing for the realization of traffic engineered networks by introducing the principles of TE. This post focuses on describing the problem space of TE, the requirements that fall out of it, and a balanced architectural approach.

RFC 9522 Matters

Traffic engineering discussions often drift toward technical protocol advocacy and arguments rather than operational and business models. RFC 9522 is useful precisely because it avoids prescribing a specific technology and instead focuses on process: how intent is formed, how constraints are applied, and where computation should occur. What, exactly, should the network be doing?

This post builds upon RFC 9522 and proposes a traffic-engineering process model applicable to any packet network, regardless of whether the network uses MPLS, IGP metrics, static routes, segment routing, or some future forwarding paradigm. What matters is not the protocol choice, but the ordering of decisions and the separation between intent, computation, and execution.

Traffic Engineering is Not a Feature

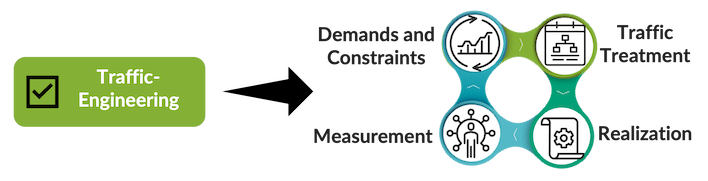

Too often, traffic engineering is considered a feature set delivered by a specific protocol or set of configurations in routers, rather than as an ongoing, cyclical operational process. The process of traffic engineering operations should encompass:

- Understanding demands and constraints,

- Deciding how network traffic should be treated,

- Allowing the network to realize those decisions dynamically, and,

- Provide data to measure the effectiveness of deployed policies.

Academic or even borderline religious arguments about various protocols and signaling mechanisms distract from the ultimate goal of an optimal network. A myopic focus on technology – at the expense of good engineering discipline – often will have the perverse result of complexity accumulating in the wrong places. The blinders prevent the visibility needed to make informed choices.

Scalable TE, that can deliver real operational and business value to networks, begins with a clean separation between what is needed and how it is executed.

Protocol Neutrality is Imperative

Neutrality in network architecture means discarding of bias and prejudice in the selection of technology, and this is especially true at the network protocol level. “No technology religion” was literally printed on the badges of employees of one of the largest routing vendors. But protocol neutrality is not an academic preference — it is an operational necessity. Because of their physicality, substrate or physical networks will evolve more slowly than the services they carry. And core packet transport mechanisms evolve even slower – often outliving multiple generations of control logic. Therefore, it is vital that intent and constraints form independently of protocol choice, so that:

- New services can be introduced without reworking the transport core,

- Different execution mechanisms can coexist or be replaced over time, and,

- Operators can evaluate technologies based on fit, not lock-in.

This neutrality ensures that the TE process remains stable even as underlying implementation details may change.

Traffic Engineering as a Process

This problem is not one of protocol scalability or control-plane efficiency. Instead, it frames traffic engineering as a decision-making process that must precede any discussion of protocols or mechanisms.

At its core, traffic engineering answers a simple question: given a set of demands and constraints, what outcomes are acceptable? The difficulty lies not in forwarding packets, but in deciding—consistently and repeatably—how traffic should be treated under normal and degraded conditions.

It is critical that intent exists before the network does anything – before there are any paths, signaling, or forwarding state. Intent represents policy, performance objectives, and operational boundaries that guide all traffic engineering decisions. Problems arise intent is bounded by or influenced by specific protocols, or artifacts such as explicit paths or device-level instructions. From a process perspective, this premature binding has several consequences:

- Decisions become tied to a specific realization rather than a set of acceptable outcomes,

- Adaptation to failures or changing conditions become constrained, and,

- Operational reasoning shifts from intent validation to protocol maintenance.

A sound traffic-engineering process preserves intent as a primary input. This keeps traffic engineering focused on decision quality rather than mechanism efficiency, and it applies regardless of the protocols used to realize those decisions.

An Intent-Aware Traffic Engineering Model

The following principles define a clean separation between decision‑making and execution. These are deliberately technology‑agnostic and describe a general TE process model.

Intent Formation with Global Context

Intent must be expressed where sufficient context exists to evaluate trade‑offs. This includes visibility into topology, capacity, and policy—but not necessarily direct control of the forwarding plane.

In process terms, this is the planning and decision phase of traffic engineering. It is where operators or automation systems decide what outcomes are acceptable and which constraints are non‑negotiable. This formation can be simulated with software to illustrate how the network is expected to behave under both optimal and suboptimal conditions.

Localized Execution and Autonomy

Once intent has been resolved into constraints, execution should remain distributed. Devices must be able to:

- React to failures without waiting for external coordination,

- Apply constraints using mechanisms they already support, and,

- Preserve fast convergence and local protection behavior.

This maps to the execution phase of the TE process, where local autonomy is preserved even though decisions were informed by global reasoning and simulation.

Logical Constraints not Protocol Extensions

Lastly, a key requirement of this model is that intent should be expressed through composition of existing attributes rather than continual protocol extensions. This applies regardless of control‑plane technology. Constraints remain logical constructs, not protocol features.

The Traffic Engineering Taxonomy

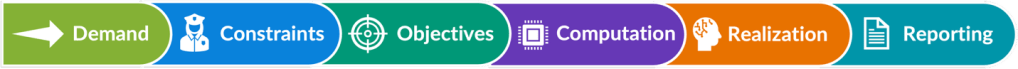

To describe traffic engineering, it is useful to break it down into a small set of conceptual building blocks. These elements form a taxonomy that clarifies what decisions are made, when they are made, and what inputs they depend on, independent of protocol or architecture.

Demand

Demand describes what traffic needs to be carried. This may be expressed at different granularities—flows, aggregates, services—but it is always an input to the TE process, not an outcome of it. Demand is descriptive, not prescriptive. It captures volume, endpoints, and traffic characteristics without implying how the network should satisfy those needs.

Constraints

Constraints define the boundaries within which demand must be satisfied. These include performance objectives, policy limitations, and resource bounds. Importantly, constraints restrict the solution space without defining a specific solution. They represent what must be true of an acceptable outcome, not how that outcome is achieved.

Objectives

Objectives describe what the TE process is trying to optimize when multiple acceptable outcomes exist. Examples include minimizing latency, balancing utilization, or maximizing resilience. Objectives are evaluated during decision-making, not enforced directly by the network. They guide selection among feasible options once constraints have been applied.

Computation

Computation is the act of evaluating demand, constraints, and objectives against the current network state to identify acceptable outcomes. This step requires global visibility and consistent logic, but it does not imply centralized execution. Computation produces decisions, not forwarding behavior. This can be an integral part of a deployed and operational network, and it can be part of a network planning process to simulate how the network is expected to behave.

Realization

Realization is the translation of decisions into executable form using the mechanisms available in the network. This is where protocols, signaling, and local behaviors come into play. Realization is intentionally decoupled from decision-making so that execution can remain distributed, resilient, and implementation specific.

Reporting and Measurement

Support and validation of the TE system through scalable reporting and real-time measurement is critical. Both short- and long-term traffic statistics are essential for gleaning information such as busy-hour characteristics, traffic growth patterns, persistent congestion problems, and imbalances in link utilization. These measurements ultimately provide meaningful and reliable indicators of the realization of the TE process.

Closing Thoughts and Practical Takeaways

Taken as a whole, this traffic engineering model emphasizes decision ordering over mechanism choice. By separating intent formation, evaluation, and realization, operators gain clarity without sacrificing flexibility.

Several practical takeaways follow:

- Traffic engineering starts with demand, constraints, and objectives – not protocols

- Execution mechanisms should remain interchangeable

This way of thinking shifts the focus from how paths are signaled to how decisions are made, which is ultimately where correctness and operational simplicity are determined.

RFC 9522 is valuable not because it promotes a particular architecture, but because it provides a clear framework for reasoning about intent, constraints, and computation boundaries. When those boundaries are respected, networks can evolve without repeatedly rediscovering the same scaling and operational pitfalls. The architectural lesson stands on its own, independent of any specific protocol or deployment model.

Disclaimer

The opinions, analyses, and recommendations expressed in any post, comment, or other content on tedigest.com are solely those of the individual authors. They do not represent the official policies, positions, or endorsements of the authors’ current or former employers and affiliated organizations.

Leave a comment